CLAS 301B

February 11, 2025

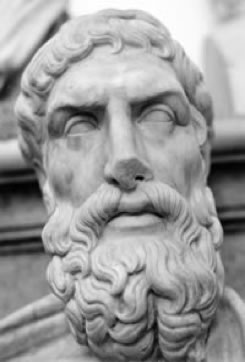

Roman copy of bust of Epicurus

Examination #1 Study Guide

(Thursday, February 20)

Titus Lucretius Carus (94-55 BCE): no reliable biography (claim that Lucretius driven insane by love-potent is Christian polemic); patron Memmius ("the governor liked to / fuck you in the mouth", Catullus 10.11-12); writing "when our country is in trouble" (1.42)

• De Rerum Natura/On The Nature of Things: 6 books (dactylic hexameter) on teachings of “god-like” philosophical & cosmic hero Epicurus (341-270 BCE; lost Concerning Nature), e.g. "the vital force of his mind was victorious, / and he traveled far beyond the flaming walls of the world / and trekked throughout the measureless universe in mind and spirit", 1.72ff.); Epicurus' Garden (Athens), 3 letters, quoted maxims & fragments extant, Lucretius' poem our fullest exposition of Epicureanism

• Epicurean "nature" (Latin natura/Greek physis): abstract guiding principle of creation & life, knowledge of nature's workings gained through senses aided by reason

• Epicurean materialism (Democritus, 5th century BCE): matter = indivisible, indestructible, eternal particles, Greek atomoi (“un-cutables”); everything the result of combination of atoms made possible by "the swerve" (explanation of human free will/voluntas – "a beginning of motion is created in the heart, / and comes forth first from the will of the mind, / and then is conveyed through the whole body and limbs" vs. determinism, 2.269-71) – what happens to our atoms when we die?

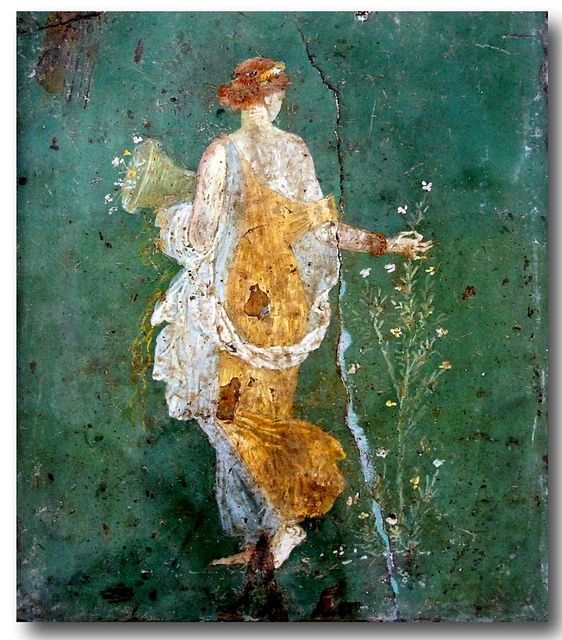

Roman Goddess Flora (Pompeii, 1st century CE)

- Epicurean ethics: painless pleasure & ataraxia (“calm”), friendship, simple life & therapeutic care of self = detached & contemplative living in accordance with nature, study of nature

On the Nature of Things 2.1-33 (disconnecting from chaos, including traditional epic pursuits)

Sweet it is, when the wind whips the water on the great sea,

to gaze from the land upon the great struggles of another,

not because it is a delightful pleasure for anyone to be distressed,

but because it is sweet to observe those evils which you lack yourself.

Sweet, too, to gaze upon the great contests of war

staged on the plains, when you are free from all danger. [cf. Iliad]

But nothing is more delightful than to possess sanctuaries

which are lofty, peaceful, and well fortified by the teachings of the wise.

From there you can look down upon others and see them lose

their way here and there and wander, seeking a road through life,

struggling with their wits, striving with their high birth,

exerting themselves night and day with outstanding effort

to rise to the level of the greatest wealth and to have mastery over things. [cf. Odyssey]

O wretched minds of men, o blind hearts!

In what darkness of life and in what great dangers

this little span of life is spent! Don’t you see

that nature cries out for nothing except that somehow

pain be separated and absent from the body, and that she enjoy in the mind

pleasant feelings, and be far from care and fear?

Therefore we see that there is need for very little

for our bodily nature, just enough to take away pain

and also to spread out many delights before us.

Nor does nature itself ever ask for anything more pleasing,

if there are no golden statues of youths in the halls, [cf. Odyssey 7.100ff., Phaeacians]

holding fire-bearing torches in their right hands,

so illumination can be supplied for banquets at nighttime,

if the house does not gleam with silver and shine with gold,

and if the gilded and paneled roof timbers do not resound with the lyre,

when nevertheless people lie in groups on the soft grass

beside a stream of water beneath the branches of a tall tree

and at little expense delightfully tend to their bodies,

especially when the weather smiles and the seasons of the year

sprinkle the green-growing grass with flowers.

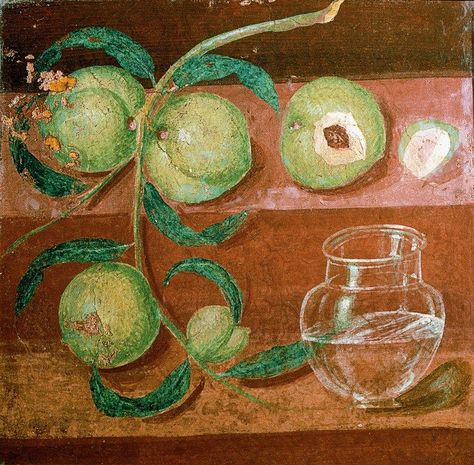

Still life peaches (Herculaneum, 1st century CE)

• Epicurus' condemnation of poetry (after Plato et al.): Lucretius recalls Hesiod (Theogony, Works & Days, 8th century BCE) & tradition of didactic epic poetry, Empedocles' philosophical poems (5th century BCE) & Alexandrian scholar-poets' scientific poems, e.g. Aratus' Phaenomena (astronomy)

- Lucretius' archaizing Latin (after "our Ennius", 1.117): dress non-traditional thought in traditional form ("Ennius trap"); alliteration & assonance, sonorous, old-fashioned epic compounds (e.g. "ship-bearing"/navigerum, "fruitful"/frugiferentis, 1.3), rich word-play; Ennius (239-169 BCE), Annales still Roman national epic (cf. Ennius' didactic works on Euhemerism); Lucretius to correct Ennius' "errors" (esp. soul's reincarnation, 1.116ff.)

Friedrich von Thiersch Saal, Dancing Muses (2013)

- Why poetry? (Muses & medicine)

On the Nature of Things 1.921-50

(READER: Nicholas)

Now come, understand what remains and hear more clearly.

I am very aware how obscure these things are. But great

hope for praise strikes my heart with a sharp thyrsus

[wand of Dionysus]

and at the same time strikes into my breast sweet love

for the Muses. Now roused by this in my lovely mind

I am traversing the remote places of the Pierides, untrodden by the sole

of anyone before. It is a joy to approach pure springs

and to drink from them, and it is a joy to pick new flowers

and to seek a preeminent crown for my head from that place

whence the Muses had wreathed the temples of no one before;

[Alexandrian novelty]

first because I am teaching about great things and proceeding

to free the mind from the narrow bonds of religion,

next because I am writing so clear a poem about so obscure

a subject, touching everything with the charm of the Muses.

For this too seems to be not without reason.

But just as when physicians try to give loathsome wormwood

[absinthia]

to children, they first touch the rim of the cup all

around with the sweet, golden liquid of honey,

so that the unsuspecting age of children may be tricked as far

as their lips, and so that meanwhile the child might drink down

the bitter wormwood juice and though deceived, be not deceased,

but rather by such means be restored and become well,

so I now, since this system seems for the most part to be

too bitter to those who have not tried it and

the common people shrink back from it, I wanted to explain

our system to you in sweet-spoken Pierian song

and touch it, so to speak, with the sweet honey of the Muses.

I have done so in the hope I might in this way be able to hold

your attention in our verses, until you look into the whole

nature of things, with what shape it is endowed and exists.

Detail of mosaic from Tunisia (2nd century CE)

- Lucretius’ passionate, proselytizing dialogue with Memmius/the reader (2nd person singular), plea for receptiveness to ideas (e.g. on existence of other worlds, 2.1023ff. ):

On the Nature of Things 1.400-9 (on existence of void)

. . . by relating many arguments to you I am able

to scrape together trust in these words of mine.

But these little traces are enough for a keen intellect,

and by their means you are able to discover the rest on your own.

For just as dogs often find with their noses the resting places,

covered by foliage, of a wild beast that roams the mountains,

as soon as they set to work on the sure traces of its path,

so you yourself on your own will be able in such cases

to see one thing from another and to work your way into every

dark hiding place and drag back the truth from them.

- Lucretius' accumulation of proofs (Groups)!

- mixed reception of Lucretius: Epicureanism potentially counter to Roman tradition of public life & state religion – Epicurean attack on religio focused on divine intervention & fear of death – spurned as radical thinking by some, but Epicurean philosophy enjoys popularity in Rome (unpopular with Christian apologists, in favor with Renaissance humanists & during European anti-theist enlightenment

; cf. Stephen Greenblatt's The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, 2012)

- Epicureanism not atheist

On the Nature of Things 1.44-9 (transition from hymn to Venus to Epicurean philosophy & detached gods)

For it must be that the entire nature of the gods

spends everlasting time enjoying perfect peace,

far removed and long separated from our concerns.

For free from anxiety, free from dangers,

powerful in its own resources, having no need of us,

it is not won over by the good things we do nor touched by anger.

Aphrodite of Melos/Venus de Milo (late 2nd century BCE)

• opening traditional hymn to Venus: contradictory “Venus flytrap” to draw readers to study of nature (Venus as symbol of nature?)

Venus Fresco (Pompeii, Casa di Venus)

On the Nature of Things 1-30 (Venus' procreative powers)

Mother of the descendants of Aeneas, pleasure of humans and gods,

life-giving Venus, it is you who beneath the gliding signs

of heaven makes the ship-bearing sea and the fruitful earth

teem with life, since through you the whole race of living creatures

is conceived, born, and gazes on the light of the sun.

You, goddess, you the winds flee, you the clouds

of the sky flee at your coming, for you earth the artificer

sends up her sweet flowers, for you the expanses of the sea smile,

and the heavens, now peaceful, shine with diffused light.

For as soon as the sight of a spring day is revealed,

and the life-bringing breeze of the west wind is released and blows,

the birds of the air are the first to announce your arrival,

o goddess, overpowered in their hearts by your force.

Next wild beasts and flocks prance about their glad pastures

And swim across rushing streams. So taken by delight

Each follows you eagerly wherever you proceed to lead them.

Then through the seas and mountains and fast-clutching rivers,

through the leaf-thronged home of birds and verdant plains,

you strike, injecting sweet love in to the hearts of all,

and make them eagerly create their offspring, each according to kind.

Since you alone guide the nature of things

and without you nothing emerges into the sunlit shores

of light, nothing glad or lovely comes into being,

I am eagerly striving for you to be my ally in writing these verses

that I am trying to set out about the nature of things

for our illustrious son of the Memmii, whom you, goddess, on every

occasion have wished to be preeminent, adorned with every blessing.

All the more endow these words with everlasting charm, goddess.

Meanwhile, make it so that the savage claims of war

are put to sleep and lie quiet throughout every sea and land.

[Venus' quasi-erotic calming of anthropomorphic Mars follows]

_-_Napoli_MAN_9112_-_01.jpg)

Iphigenia’s Sacrifice (Pompeii, 1st century CE)

• opening hymn capped with myth of Agamemnon's sacrifice of Iphianassa/Iphigenia (Greeks at port of Aulis) – religion's impiety

On the Nature of Things 1.84-100 (READER: Morgan)

Thus was the case at Aulis, when the chosen leaders of the Greeks,

the first among men, foully defiled the altar

of the virgin goddess of the crossroads with the blood of Iphianassa.

As soon as the sacrificial headband was wreathed about her virgin locks

with its streamers

flowing equally from both her cheeks,

and as soon as she saw her father standing in mourning before the altar,

with his attendants beside him concealing the iron blade,

and the citizens pouring forth tears at the sight of her,

speechless with fear she sank in her knees and fell to the ground.

Nor was it a help to the wretched girl at such a moment

that she had been the first child to call the king "father".

She was lifted up by men's hands and led trembling,

to the altar, not so that she might be greeted by the loud-ringing

marriage hymn when the solemn wedding rite was finished,

but that the chaste girl might be slaughtered unchastely at the very point

of marriage, a grieving victim, by the sacrificial stroke of her father.

All this so that a happy and auspicious departure might be granted to the fleet.

- Lucretius on lack of Latin philosophical/scientific language, e.g. no word for “atoms" = semina rerum ("seeds of things"), materies ("primary matter"), corpora prima ("first bodies"), genitalia corpora ("generative bodies") et al. (Lucretius avoids borrowings of Greek words)

On the Nature of Things 1.136ff.

Nor does it escape my thought that is difficult to throw light

upon the obscure discoveries of the Greek in Latin verses,

especially since we must use new words for many things

because of the poverty of our language and the newness of the subject matter

. . .

GROUPS

_-_Napoli_MAN_9112_-_01.jpg)