CLAS 301B

February 13, 2025

Study Guide for Examination #1 (Thursday, February 20)

Lucretius, De Rerum Natura (cont.)

- On the Nature of Things 3: materiality of soul ( = consciousness) & separation from body at death, “Therefore death is nothing to us nor does it concern us at all . . . ” (3.830); acceptance of death critical to ataraxia – Nature's diatribe against humankind, "What is so troublesome to you, o mortal, that you indulge too much in / anxious lamentations? Why do you groan and bewail death? . . . why do you not why not depart like a banqueter who is sated with life?" (3.932ff.)

Litovchenko, Charon Carrying Souls across the River Styx (1861)

- mythico-poetic underworld rationalized/psychologized as projection of human fears & anxieties: Tantalus ("fears the boulder hanging in the air", 3.981)? Tityos ("[not] lying in Acheron whom birds /root around", 3.984-5)? Sisyphus ("here in life before our eyes", 3.995)? Furies?

- consolation for mortality: Xerxes, Scipio, Homer, Democritus, and even ? died ("Will you then really be hesitant and angry at dying?", 3.1024ff.)

- fear of death: constant anxiety & fear cause of antisocial & criminal behavior, including "civil bloodshed" (3.70)

On the Nature of Things 3.1060-1070 (psychological effects of fearing death)

The man

who is sick and tired of his home

often leaves his mansion, and then suddenly returns,

since he feels things are not at all better outdoors.

Driving his imported ponies he races to his country villa

at top speed, as if rushing to bring help to a house on fire.

He

immediately starts yawning when he touches the threshold of his villa,

or goes off into a heavy sleep and just tries to forget,

or dashing off again he seeks to return to the city.

Thus each person flees himself, but he cannot, of course,

escape the one he flees, but clings to him unwillingly and hates him

because he is sick and does not understand the cause of his disease.

- On the Nature of Things 4: materiality of perception, thought, senses – images (simulacra) are material; Epicurean explanation of sleep & images in dreams (4.907-1051) > dangers of love/desire (disease, impossibility of satiety/pure pleasure without pain, lover deceived by images, etc.); female sexuality, (in)fertility, heredity

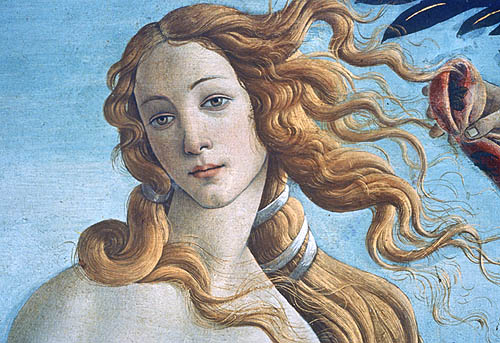

Botticelli, Birth of Venus (ca. 1485)

- romantic love: pursuit of insubstantial images whether lover present or absent (cf. representation vs. reality, virtual existence); advice for the lovesick

On the Nature of Things 4.1052-1072 (READER: Tori)

So therefore he who receives wounds from the weapons of Venus,

whether a boy with womanly limbs strikes him

or a woman radiating love with her whole body,

from where he is struck, there he tends and longs to have intercourse

and to send fluid drawn from his body into the other body.

For silent desire gives forewarning of future pleasure.

This is our Venus. From this too is the name of love,

From this that drop of sweet Venus first trickled

into our hearts and frigid care came after.

For if what you love is absent, still there are images available

of it, and its sweet name makes its way to your ears.

But it is fitting to flee the images and to drive off from yourself

what nourishes love and to turn your mind elsewhere

and to send your fluid, gathered together, into whatever body,

and not to retain it, once troubled by the love of one,

nor to cause care and certain pain to continue for yourself.

For the sore is kept alive and grows older by feeding

and daily the madness swells and the affliction grows worse,

unless you overwhelm the first wounds with fresh blows

and, wandering to a widely-wandering Venus, cure them while fresh

or are able to direct the motions of your mind in a different direction.

- permissible Epicurean love: a Valentine's Day message from Lucretius!

On the Nature of Things 4.1278-87 (love & erosion)

Sometimes neither by divine agency nor by the shafts of Venus

it happens that a woman of lesser worth and beauty is loved.

For sometimes a woman herself by her very own actions

and compliant ways and neatly groomed body makes it

so that she easily accustoms you to spend your life with her.

What is more, close familiarity brings love into existence.

For however lightly anything is struck by frequent blows,

it is yet overcome in a long period of time and yields.

Don’t you also see that drops of liquid falling

on rocks bore through the rocks in a long period of time?

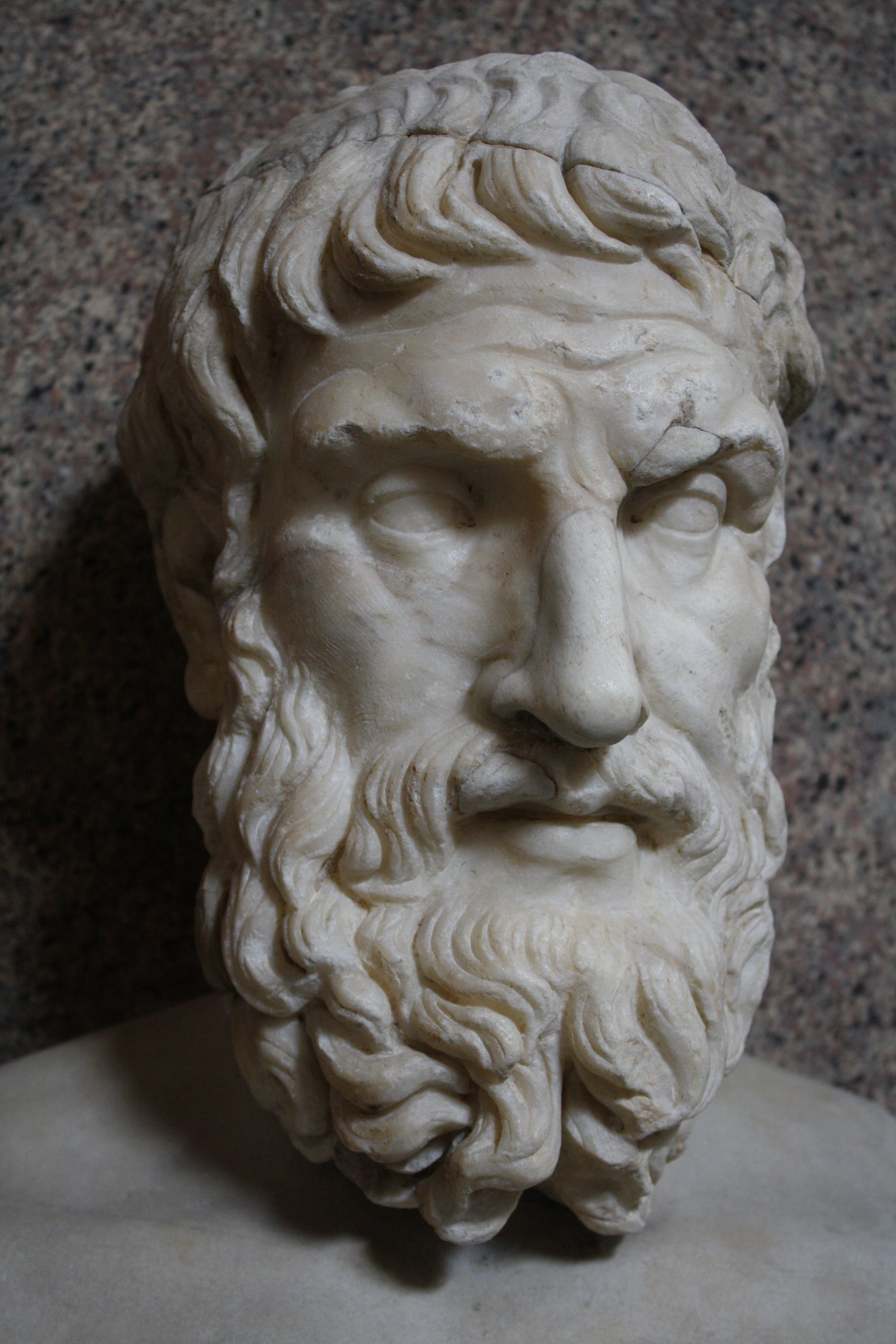

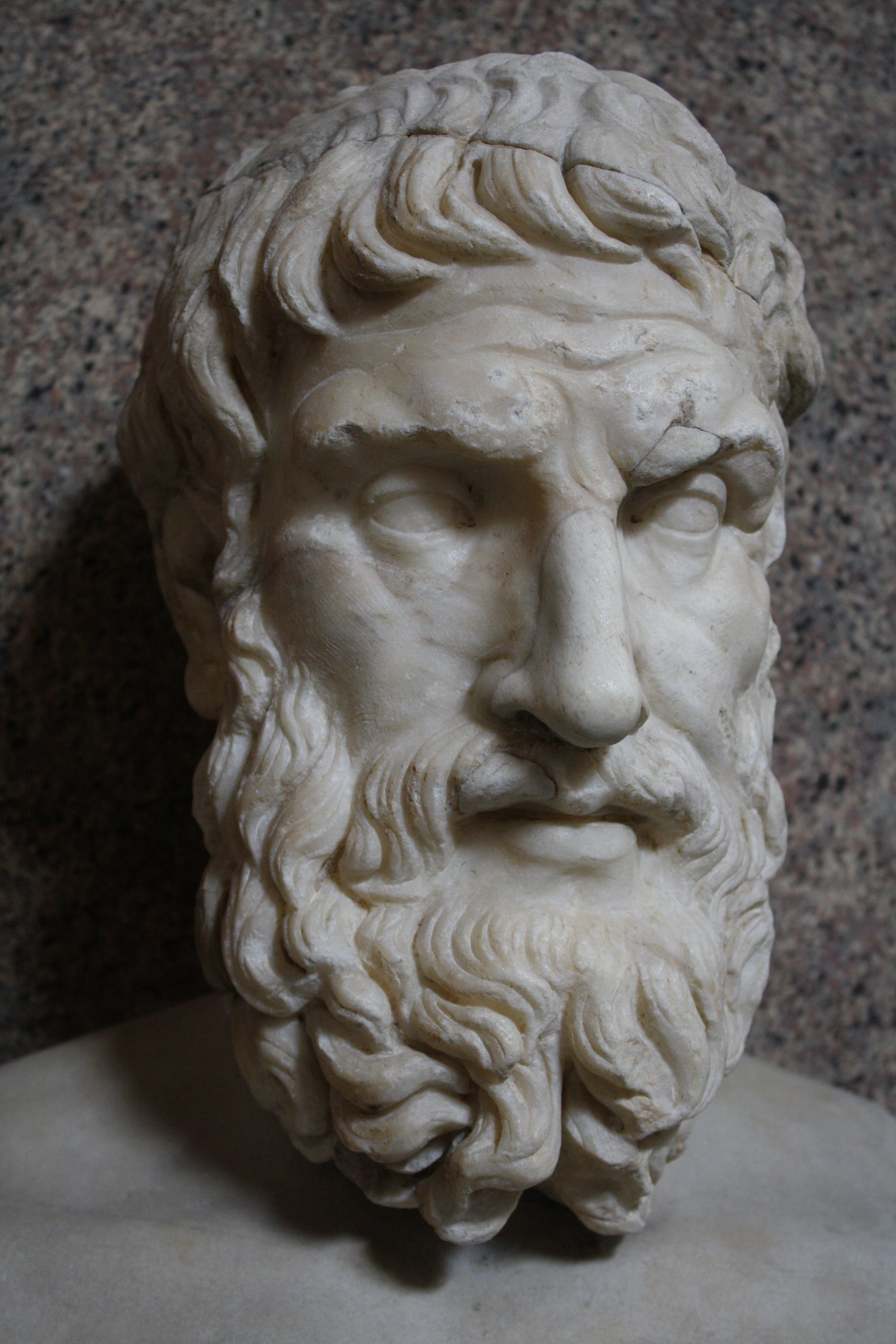

L: bust of Epicurus (Roman copy); R: Hercules (3rd century CE)

- opening of On the Nature of Things 5: Epicurus as god-like, epic-cosmic/pathfinding culture hero ("the walls of the world

/

dissolve, I see things carried along through the whole void," 5.17-18), comparison with Hercules (labors, 5.24-36)

On the Nature of Things 5.37-54 (READER: Duncan)

And all the other monsters of this kind which were destroyed,

if they were not vanquished before, what harm could they do us if alive?

None, I think: so the earth even now teems to fullness

with wild beasts and is filled with trembling terror

throughout groves and great mountains and deep forests.

Most of the time it is in our power to avoid these places.

But unless our mind is washed clean, then what battles

and dangers must we be involved with against our will?

How many sharp cares of desire carve up

a human being in distress, and equally how many fears?

Or what of pride, filthy avarice, and arrogance? How many

disasters do they bring about? What of soft living and idleness?

Therefore he who subdued all these things

and drove them from the mind with words, not arms—isn’t it fitting

that this human be deemed worthy of being numbered among the gods?

Especially since he was accustomed to write many words

well and in a godlike way about the immortal gods themselves

and to lay open the whole nature of things with words.

- On the Nature of Things 6: physics of weather & (destructive) terrestrial phenomena (e.g. earthquakes); disease (caused by deadly seeds, not gods) > closure with plague at Athens (430 BCE; cf. Thucydides, Peloponnesian War 2.47-55)

- epidemic as ultimate test of religious beliefs

On the Nature of Things 3.55-58:

Wherefore it is more effective to gauge a person in times

of doubt and danger, and to learn what they are like in adversity.

For then at last real voices are extracted from the bottom

of the heart and the mask is ripped off: reality remains.

Arnold Böcklin, Plague (1898)

- horror of plague

On the Nature of Things 6.1250-1271 (READER: Alexandria)

Nor was anyone able to be found whom disease or death

or grief had not affected badly at so terrible a time.

Now, moreover, the shepherd and every herdsman,

and likewise the strong wielder of the curved plow, drooped

from weakness, and their bodies lay piled up deep

within their huts, handed over to death by poverty and disease.

At times you were able to see the lifeless bodies of parents

on top of their lifeless children, and conversely, you could see children

taking their last breath on top of their mothers and fathers.

This affliction flowed in no small part

from the country into the city, for the weakened and diseased band

of farmers brought it with them as they arrived from every direction.

They filled all spaces and houses, so that all the more

with the heat death was heaping them packed together in piles.

Many bodies, prostrate from thirst and toppled over

in the street, lay strewn by the Silenus water fountains.

Their breath was choked off by excessive allure of water.

And many you would see scattered throughout the public places

and roads, drooping limbs with bodies barely alive,

studded with muck and completely covered with rags, dying

from bodily filth, nothing more than skin and bones,

nearly buried already by foul ulcers and scum.

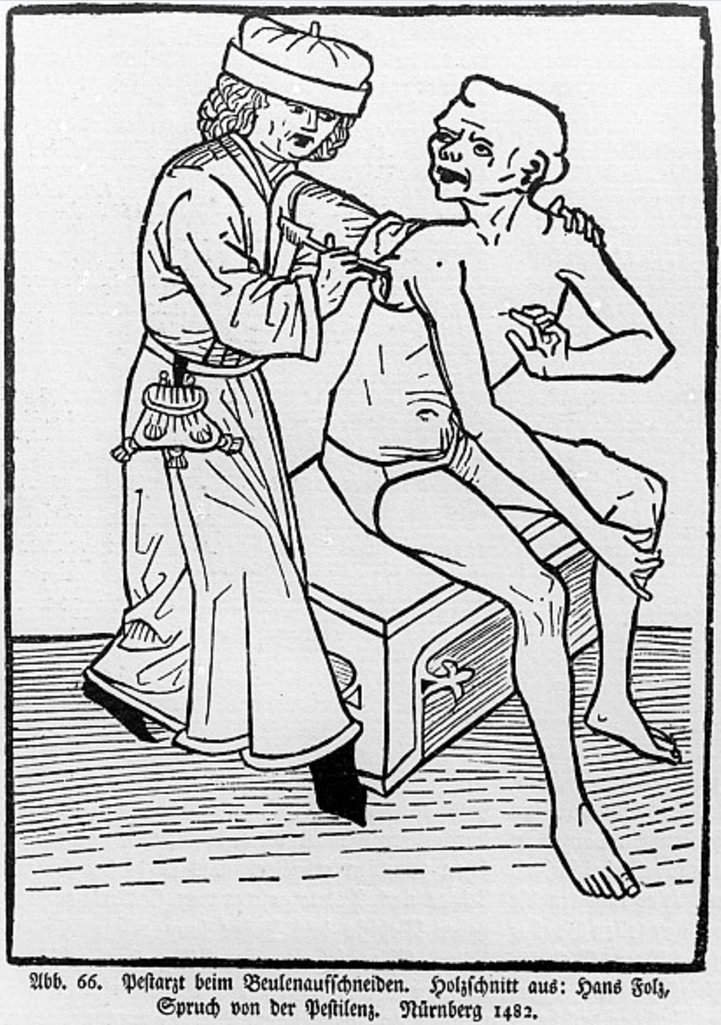

Woodcutting of a bubo being lanced (15th century)

- contrasting human responses

On the Nature of Things 6.1205-1212 (effects of fear of death)

Further, for the one who escaped the fierce discharge of foul

blood, the disease still travelled into the sinews

and limbs, and even into the genital parts of the body.

And some, fearing with great severity the threshold of death,

continued to live once their manly parts were cut off

by the knife, and others yet remained in life without benefit

of hands or feet, and some suffered the loss of their eyes:

so far had the piercing fear of death come over them.

On the Nature of Things 6.1237-1245 (the virtuous: community & compassion in death)

For whoever avoided going and seeing their own sick

excessively greedy for life and being afraid of death.

was punished soon after by slaughtering neglect

with a foul and evil death, abandoned and without aid.

But those who stayed around to help died from contagion

and the labor that shame forced them to undergo,

and the coaxing voice of the sick mixed with the voice of lamentation.

The most virtuous people underwent this type of death.

- panicked collapse of civil society & community, false beliefs about gods exposed – temples?

On the Nature of Things 6.1276-1286 (poem's closing images of fear & anxiety)

Nor indeed any longer was reverence of the gods or their divinity

of much worth: the present grief was completely overwhelming.

Nor did those burial rites continue in the city, with which

these people before were always traditionally buried.

For the whole populace was perturbed and in a panic, and each one,

grieving, buried his own dead hastily, as time allowed.

The suddenness of events and poverty led to so many horrible actions.

For they placed their own blood-relatives with tremendous wailing

on top of funeral pyres heaped high for others

and set torches beneath them, often violently quarreling

with great bloodshed rather than desert the bodies.

practice commentary (Examination #1):

For if what you love is absent, still there are images available

of it, and its sweet name makes its way to your ears.

But it is fitting to flee the images and to drive off from yourself

what nourishes love and to turn your mind elsewhere

and to send your fluid, gathered together, into whatever body,

and not to retain it, once troubled by the love of one,

nor to cause care and certain pain to continue for yourself.

For the sore is kept alive and grows older by feeding

and daily the madness swells and the affliction grows worse,

unless you overwhelm the first wounds with fresh blows

and, wandering to a widely-wandering Venus, cure them while fresh

or are able to direct the motions of your mind in a different direction.

(1) identify the author;

(2) identify the work from which the passage is taken;

(3) identify the speaker(s) of the passage;

(4) briefly describe the context in which the passage occurs;

(5) write a carefully organized essay/short answer commenting on the larger significance of the passage in light of the work’s main themes, its characters, its historical, social-historical, or literary-historical significance, literary qualities, style and techniques, ideas, etc.