CLAS 355

Nature's Traumas (Fires & Epidemics)

April 11, 2023

Hubert Robert, The Fire of Rome, 1785

Response #2 (due April 21); Topics

Volcanos (Mt. Vesuvius, cont.)

- Pliny the Younger's description of flight of victims on second day (August 25, 79 CE) in Misenum: trauma, despair & rumors

Pliny, Letters 6.20.13-15 (Pliny & party step off the road)

We had scarcely sat down when darkness descended. It was not like a moonless or cloudless night, but like being in an enclosed place where the light had been doused. You could hear women moaning, children howling, and men shouting; they were crying out, some seeking parents, others children, and others wives, or recognizing them by the sound of their voices. Some were lamenting their own misfortune, others that of their families. A few in their fear of death were praying for death. Many were raising their hands to implore the gods, but more took the view that no gods existed anywhere, and that this was an eternal and final darkness hanging over the world. There were some who magnified the actual dangers with invented and lying fears. Some persons reported that one part of Misenum was in ruins, and that another was on fire; it was untrue, but their listeners believed it.

- Pompeii: frozen in time 24-25 August 79 CE, monument to the everyday

2021 discovery of slaves' quarters: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/slave-quarters-new-discovery-pompeii-2031370

"Vesuvius: The Catastrophe of Pompeii" (Timeline, 2018): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOEBVWc8crI

Fires

L: Temple of Vesta, near Tiber River in Rome, 1st century BCE; R: Vestalis Maxima, 2nd century CE

- fire a powerful divine force: Vulcan;Vesta, goddess of hearth, Vestal Virgins (six models of purity, 30 yrs. celibacy) tend her eternal fire in Roman forum temple

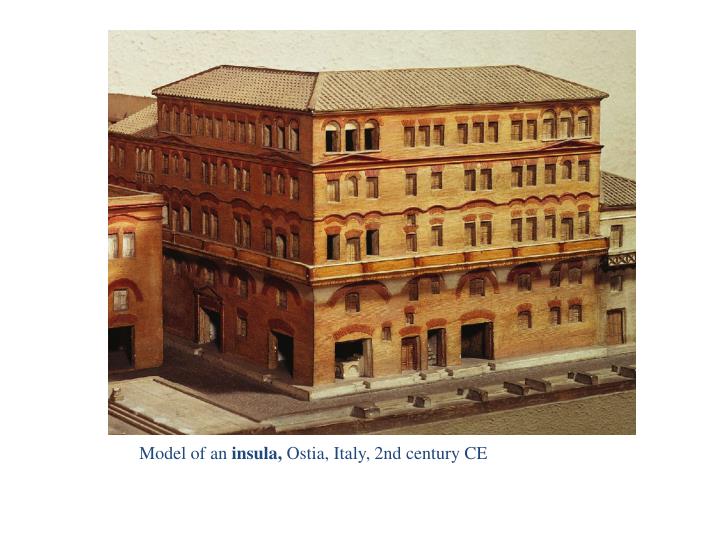

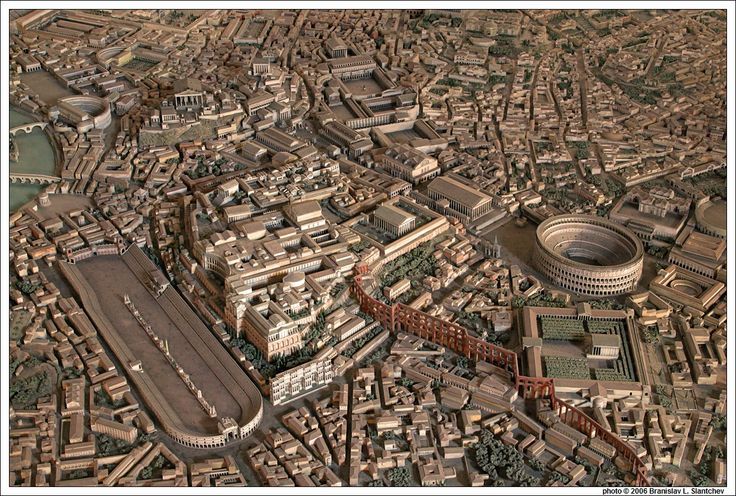

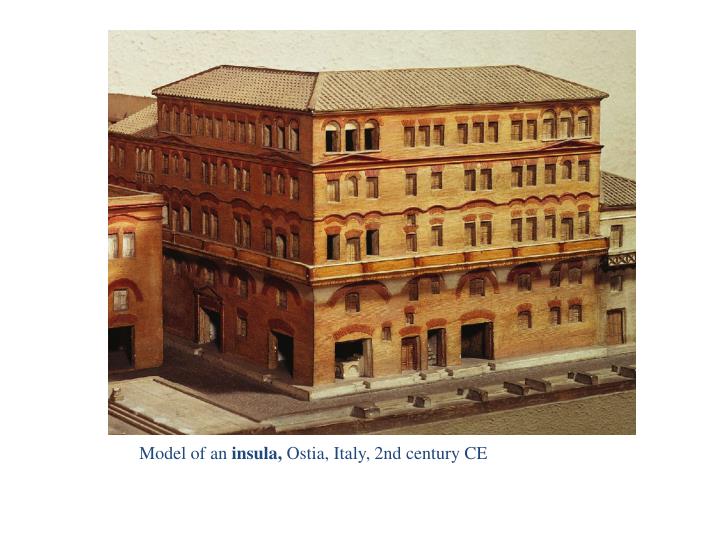

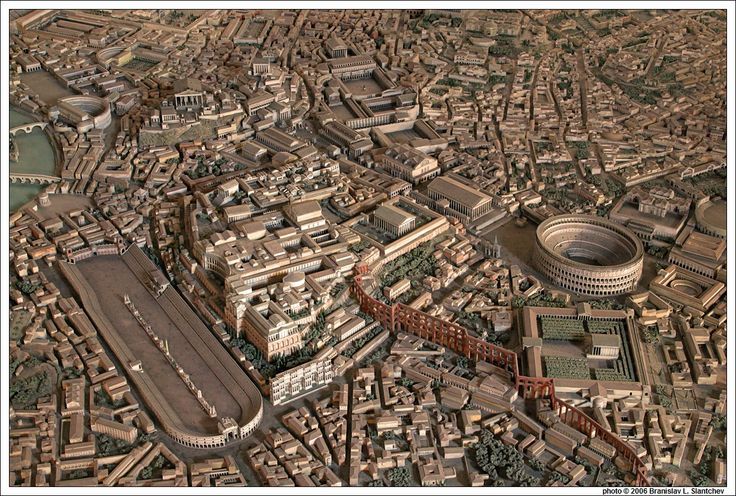

- enormous fires in Rome (Nero's in 64 CE): sections of city destroyed, deaths, displacements; wood construction of insula ("island"); open flames in dense housing vs. domus of wealthy (stone walls & structures, heating systems, indoor plumbing, flush toilets, etc.); warehouses & granaries full of flammable materials

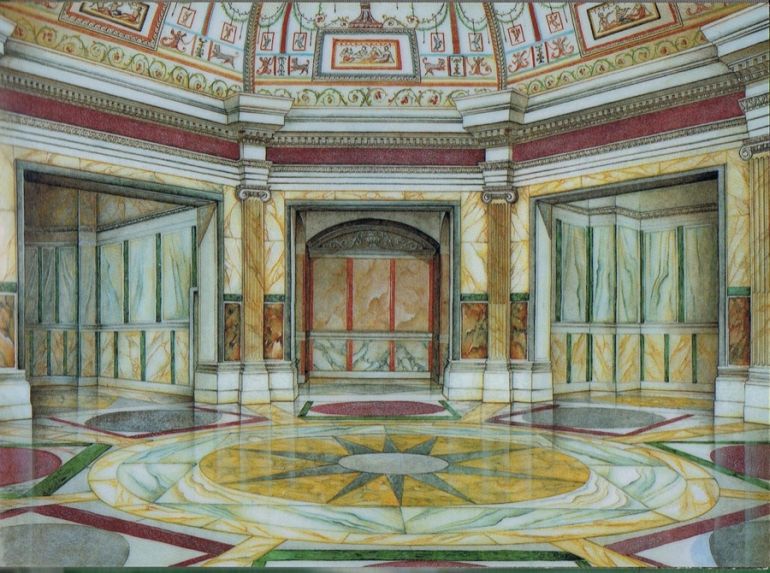

- Nero's fire (July 18, 64 CE): harnessing fire in the service of megalomania

Tacitus, Annals 15.38

It took its rise in the part of the Circus touching the Palatine and Caelian Hills; where, among the shops packed with inflammable goods, the conflagration broke out, gathered strength in the same moment, and, impelled by the wind, swept the full length of the Circus: for there were neither mansions screened by boundary walls, nor temples surrounded by stone enclosures, nor obstructions of any description, to bar its progress. The flames, which in full career overran the level districts first, then shot up to the heights, and sank again to harry the lower parts, kept ahead of all remedial measures, the mischief travelling fast, and the town being an easy prey owing to the narrow, twisting lanes and formless streets typical of old Rome. In addition, shrieking and terrified women; fugitives stricken or immature in years; men consulting their own safety or the safety of others, as they dragged the infirm along or paused to wait for them . . . Often, while they glanced back to the rear, they were attacked on the flanks or in front; or, if they had made their escape into a neighbouring quarter, that also was enveloped in the flames, and even districts which they had believed remote from danger were found to be in the same plight. At last, irresolute what to avoid or what to seek, they crowded into the roads or threw themselves down in the fields: some who had lost the whole of their means—their daily bread included—chose to die, though the way of escape was open, and were followed by others, through love for the relatives whom they had proved unable to rescue. None ventured to combat the fire, as there were reiterated threats from a large number of persons who forbade extinguishing it, and others were openly throwing firebrands and shouting that 'they had their authority'—possibly in order to have a freer hand in looting, possibly from orders received.

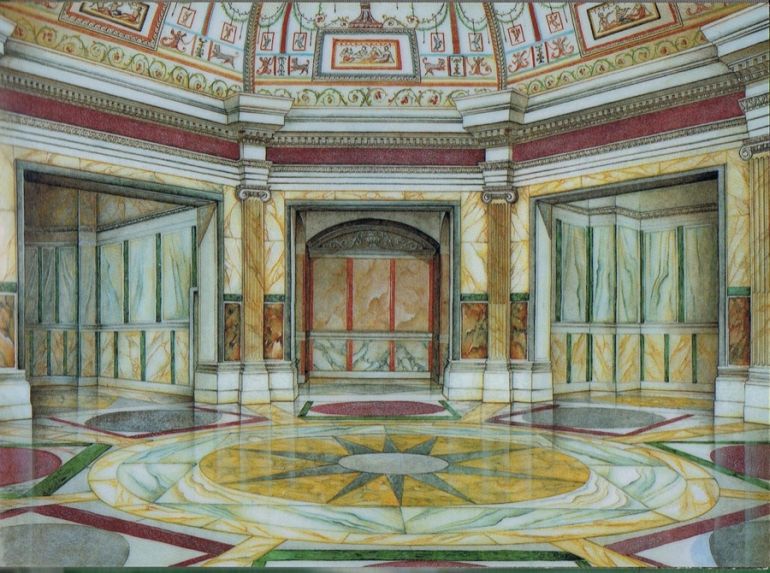

Reconstructions of Nero's Golden House

Circus Maximus & Fire (Altair4Multimedia): https://www.altair4.com/en/modelli/circo-massimo/

Rome in Flames (National Geographic): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2s7LdMk-EM4

L: Pont du Gard (Nîmes (France), 1st century CE; R: Aqueduct crossing near Rome

- imperial firefighting brigades: 7,000 paid freedmen in Augustus's time stationed throughout city; water, trenches, demolition tools; some building regulations & fireproofing measures

Tacitus, Annals 15.43 (Nero's measures after the fire of 64 CE)

. . . the districts spared by the palace were rebuilt, not, as after the Gallic fire [in 390 BCE], indiscriminately and piecemeal, but in measured lines of streets, with broad thoroughfares, buildings of restricted height, and open spaces, while colonnades were added as a protection to the front of tenement-blocks . . . The buildings themselves, to an extent definitely specified, were to be solid, untimbered structures of Gabine or Alban stone, that particular stone being proof against fire. Again, there was to be a guard to ensure that water-supply—intercepted by private lawlessness—should be available for public purposes in greater quantities and at more points; instruments for checking fire were to be kept by everyone in the open; there were to be no joint partitions between buildings, but each was to be surrounded by its own walls.

- Juvenal (ca. 60-127 CE), Satire 3: nostalgic rant by Umbricius, "Shade", as he leaves for Cumae in S. Italy & idealized countryside ("to become the proud possessor of a solitary lizard", 3.231); satirist listening, returns to city

- Umbricius's reactionary hatred of cosmopolitan Rome, 2nd century CE: immigrants, inversions of social order, resentful of social mobility, injustices/grievances of displaced "Romans", fraud, corruption, high cost of living, disparities in wealth, noise, traffic, pollution, crime & other dangers ("There's no room here for any Roman", 3.121)

- Umbricius's account of an urban fire

Crouching Lion, ca. 325 BCE (cf. Juvenal's "Chiron couchant")

Juvenal 3.193-222 (the inequities of fires)

Here we live in a city which, to a large extant,

is supported by rickety props; that's how the landlord's agent

stops its falling. He covers a gap in the chinky old building,

then "sleep easy!" he says, when the ruin is poised to collapse.

One ought to live where fires don't happen, where alarms at night

are unknown. Ucalegon's shouting "Fire!" and moving to safety

his bits and pieces; your third floor is already smoking;

you are oblivious. If the panic starts at the foot of the stairs,

the last to burn is the man who is screened from the rain by nothing

except the tiles, where eggs are laid by the gentle doves.

Cordus possessed a bed too small for Prócula, a handful

of little pots adorning the sideboard, below them a tiny

mug, and, supporting the whole, a marble Chiron couchant.

A chest, now far from new, contained some volumes of Greek;

and illiterate mice were busy gnawing the deathless verses.

Cordus had nothing. Quite. But still, the unfortunate fellow

lost that nothing—every bit of it. Then, as a final

straw on his heap of woe, when he hasn't a stitch and is begging

for scraps, no one will help him with food or lodging or shelter.

If Asturicius' mansion is gutted, the nobles appear in mourning,

their ladies with their hair dishevelled; the praetor adjourns his hearing.

Then we lament the city's disasters and rail at fire.

Before the flames are out, one comes forward with marble,

or an offer of building materials; another with nude white statues;

another presents a masterpiece of Euphránor, and bronzes

of Polyclítus, once the glory of Asian temples.

He gives books and shelves, and a Minerva to stand in the middle;

he a coffer of silver. More, and superior items

are showered on Persicus the childless magnate, who not without reason

is now suspected of having set fire to his own house.

Epidemics ("plagues")

Cloaca Maxima (sewage pipe), Rome, built ca. 600 BCE

- expansion of empire/disease: main cause of death & low life expectancy in antiquity (e.g. malaria, tuberculosis, cholera, dysentery), especially in cities; Juvenal's "slop-pails" (3.277), in-house latrines next to kitchens; sewage ditches breeding pathogens; waste-disposal in rivers, public baths, etc.; e.g. Antonine Plague (smallpox? ca. 165-180 CE, 5-10m dead?)

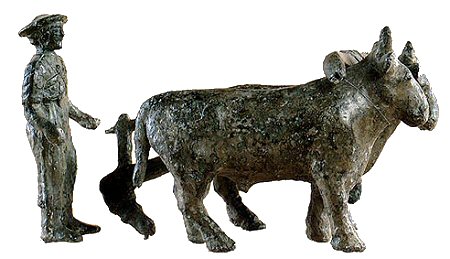

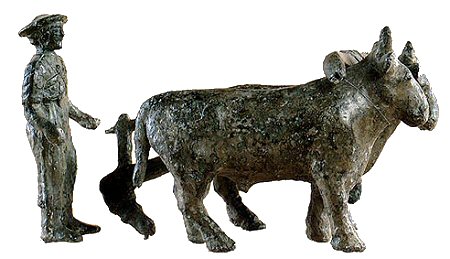

- poetic accounts of epidemics & (tragic) human condition: Vergil, Georgics (30s BCE), unexpected, massive infectious disease (morbus/pestis, "plague") afflicts livestock at end of book 3 on animal husbandry

- Vergil's anthropomorphism, the pathos of plague; sacrifice to gods impossible, medicine fails, mass burials; farmer's pessimistic world-view (futility of effort, tragedy, etc.)

Vergil, Georgics 3.515-530

See, the ox falls smoking under the plough’s weight.

and spews blood mixed with foam from his mouth,

and heaves his last groans. The ploughman goes sadly

to unyoke the bullock that grieves for its brother’s death,

and leaves the blade stuck fast in the middle of its work.

No shadows of the deep woods, no soft meadows

can stir its spirits, no stream purer than amber

flowing over the stones, as it seeks the plain: but the depths

of his flanks loosen, and stupor seizes his listless eyes,

and his neck sinks to earth with dragging weight.

What use are his labour and his service? What matter that he turned

the heavy earth with the blade? And yet no gifts of Massic wine

or repeated banquets harmed these creatures:

they graze on leaves and simple grass, for sustenance,

their drink is from clear fountains, and rivers racing

in their course, and no cares disturb their healthy rest.

- Lucretius (ca. 90-50 BCE), On the Nature of Things: philosophical poem (Epicureanism) ends with account of epidemic that struck Athens in the 5th century BCE (Thucydides); ancient "airs, waters, places theory" combined with Epicurean atomism > Egyptian plague-atoms migrate to Athens

- Epicureans: science of atomism over divine providence/religious causes/divine interventions to explain disease (cf. Seneca on earthquakes)

- Lucretius's detailed description: symptoms, suffering, death of horrific epidemic

- Epicurean ethics: friendship, therapeutic care of self to conquer anxiety, fear of death; how to behave in the face of a devastating epidemic

Lucretius, On the Nature of Things 6.1238-1246 (breakdown of interpersonal relationships & loyalty)

For

whoever avoided going and seeing their own sick,

excessively greedy for life

and being afraid of death,

was punished soon after by slaughtering neglect

with a foul and evil death, abandoned and without aid.

But those who stayed around to help died from contagion

and the labor that shame forced them to undergo,

and the coaxing voice of the sick mixed with the voice of lamentation.

The most virtuous people underwent this type of death.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Triumph of Death, 1562

Lucretius, On the Nature of Things 6.1272-1286 (breach of civility & social contract; anti-religious "proof")

At last death filled up all the holy shrines

of the gods with lifeless bodies, and everywhere all

the temples of the heavenly ones remained burdoned with corpses,

which places the temple-guardians had packed with guests.

Nor indeed any longer was reverence of the gods or their divinity

of much worth: the present grief was completely overwhelming.

Nor did those burial rites continue in the city, with which

these people before were always traditionally buried.

For the whole populace was perturbed and in a panic, and each one,

grieving, buried his own dead hastily, as time allowed.

The suddenness of events and poverty led to many horrible actions.

For they placed their own blood-relatives with tremendous wailing

on top of funeral pyres heaped high for others

and set torches beneath them, often violently quarreling

with great bloodshed rather than desert the bodies.