Classics 532

March 31, 2025

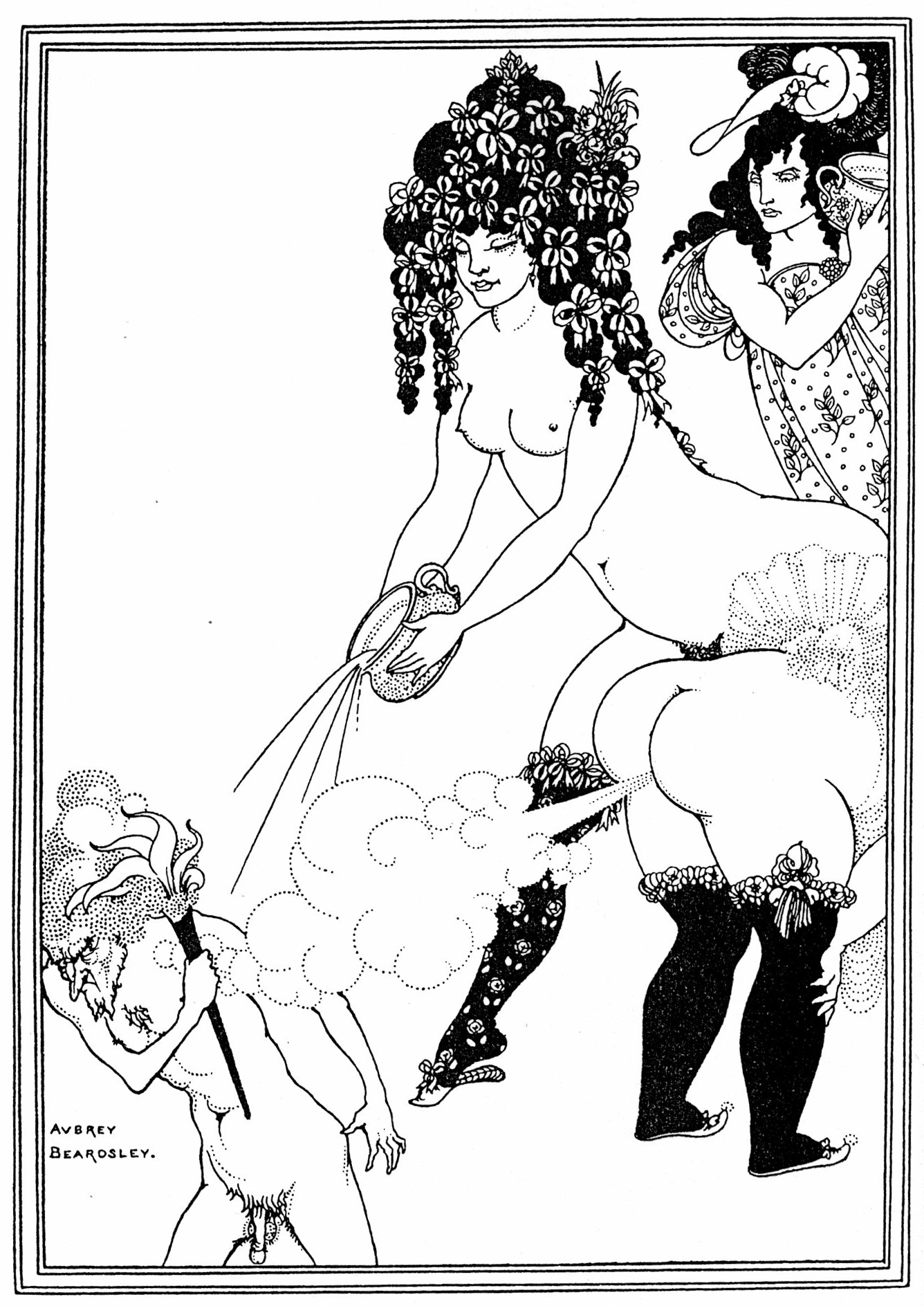

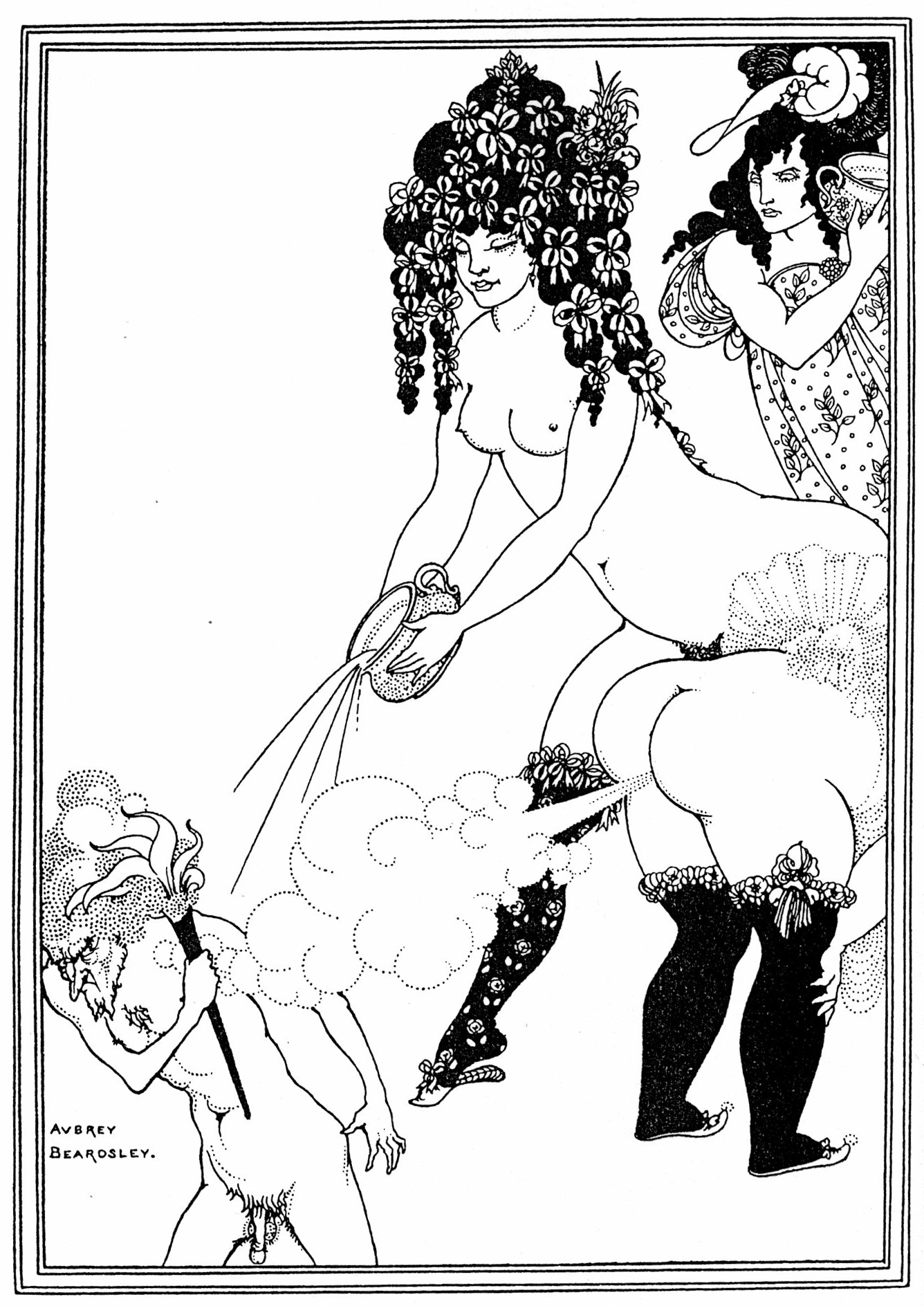

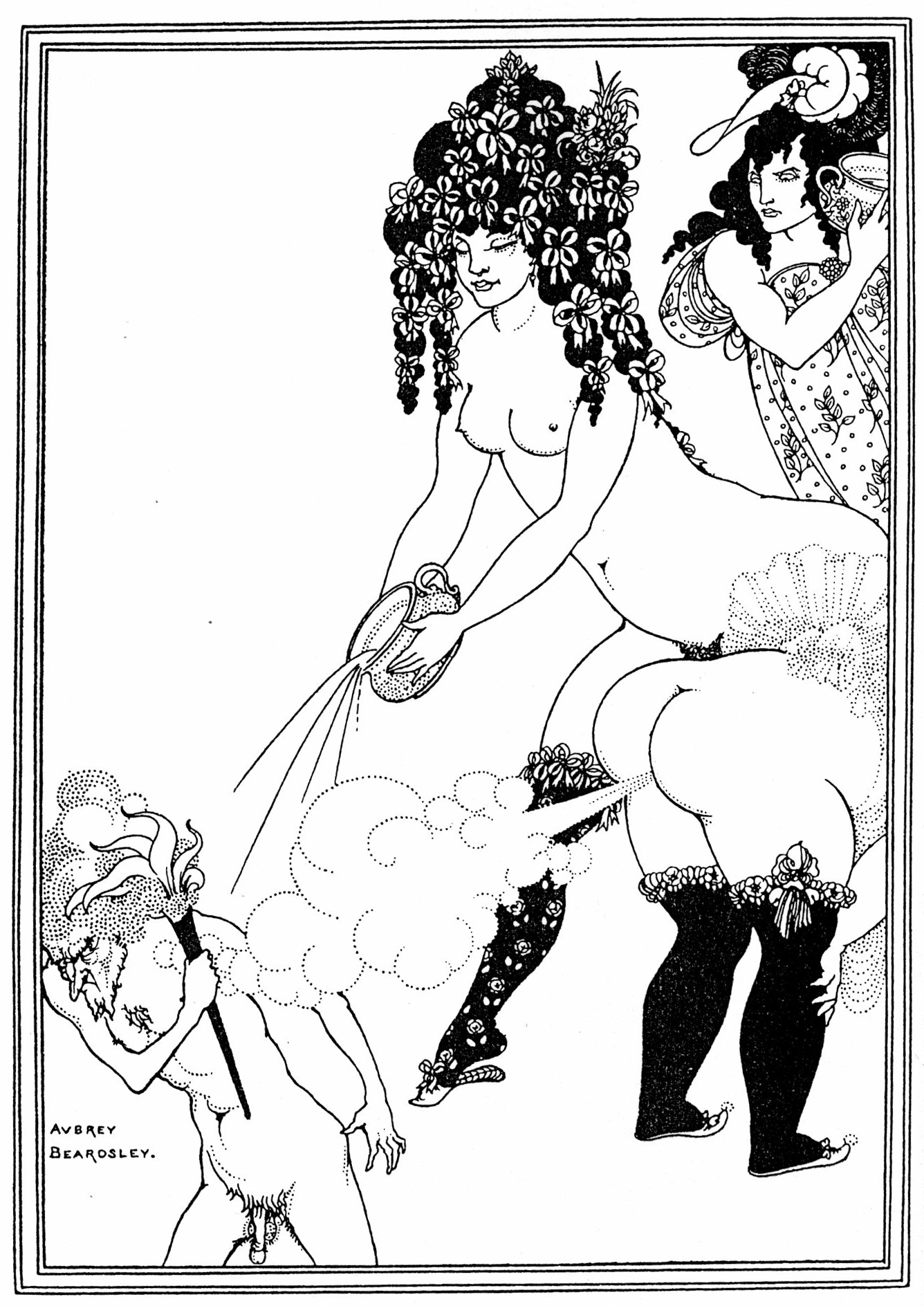

Aubrey Beardsley, “Lysistrata Defending the Acropolis” (cf. Lysistrata 350ff.; 1896 illustrations for private edition)

Beardsley’s (1872-1898), “The Lacedemonian Ambassadors” (print at The Met)

Reports (10 mins.)

Exercise #2 (due 11:59pm in D2L)

1

1

The Family Shakespeare (1807/1818)

Translating—or not—Taboos

1. Roberts, “Translation and the ‘Surreptitious Classic’: Obscenity and Translatability”: negotiating “deviant” classics (scatological & sexual content, clash of “high” and “low” culture(s) in mixed register classical texts) against TL restraints – “surreptitious classic?”

translation rationalizations, strategies & procedures for surreptitious classics (ca. 1800-1950) – main trends:

- defending the canonized classic (preserving author’s and/or text’s “moral purity”): cultural differences & distance, insignificant “good clean fun”, service of higher moral purposes (satire); mitigating procedures include bowdlerization/expurgation (removal or cleansing), obscurity/obfuscation/non-translation into TL (Latin), euphemisms, i.e. scientific equivalents, vague & moralizing generalizations of concrete ST (“filthy vice”), metonymic substitutions (“Widow’s Delight”)

- protecting readers & society from moral corruption: legal rulings & moral legislation, restricting access of “vulnerable” by status, class, gender, age (paternalism, power & privilege, class & moral assumptions), selectively disguising “low” elements in “high” characters (e.g. Lysistrata)

- acknowledging surreptitious classic as (private & privileged) guilty pleasure: obscenity vital part of classic (esp. of text's “virility”), scholarly legitimization (notes), publishing limited editions, restricted circulation

TL psycho-sexual repression of foreign materials (subversive in source culture?) vs. domestication of ST in light of target culture's social & legal restraints?

- surreptitious classic in post-pornographic, post-obscenity age? (George Carlin, “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television”, 1972; FCC guidelines on Broadcast of Obscenity, Indecency, and Profanity)

- content/trigger warnings in Classics courses reflecting sexual, ethical, legal norms of target culture

- J. Henderson, The Maculate Muse: Obscene Language in Attic Comedy (2nd edn. 1991), J. N. Adams, The Latin Sexual Vocabulary (1982) et al.

Beardsley, “Two Athenian Women in Distress” (cf. Lysistrata 716ff.)

2. Robson, “Lost in Translation? The Problem of (Aristophanic) Humour”

- Cicero’s verbal (uenustatem . . . in uerbis) vs referential (in re) distinction in intralingual translation (De Oratore 252, 258): non-punning referential humor (things, events, actions, etc.) more durable & translatable (cross-cultural assumptions; “intruded gloss”)?

- primary challenge of translating ancient humor: informative ST-adequacy vs. expressive (aesthetic, rhetorical aspects) & operative (audience effect) TL-acceptability – skopos, historicity & TL topicality, substitution, compensation, etc. (Aristophanic examples)

- humor studies & translation: systemizing (linguistics) humor theory, esp. incongruity/surprise in jokes as Raskin-Attardo's General Theory of Verbal Humour (GTVH) depending on knowledge resources = language, narrative strategy, target, situation, logical mechanism, script opposition (e.g. possible vs. impossible, non-obscene vs. obscene, non-sexual vs. sexual scripts, etc.) where punchline shifts script's frame:

“Is the doctor at home”, the patient asked in his bronchial whisper. “No”, the doctor's young and pretty wife whispered in reply. “Come right in.” (non-sexual medical-visit script > lover-visit script)

limited applicability of GTVH to translation (jokes, naivity about equivalence): knowledge resources available in target culture; networks of signification, humor & comedy's richly specific, polyvalent (performative) contexts?

1

1