CLAS 532

April 21, 2025

L: 2015 Arizona Opera production of Tchaikovsky’s opera adaptation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin; R: Arcola Theatre version, London 2017

Exercise #3 Guidelines

1. Nabokov, “Problems of Translation: Onegin in English” (1955)

- Russian expatriate’s strong reaction against “smooth” & “readable” commercial American translations of verse-novel Eugene Onegin (Russian classic, 366 stanzas of 14 lines, iambic tetrameters)

- dogmatic & extreme foreignizing model of “exact” textual translation (“the clumsiest literal translation is a thousand times more useful than the prettiest paraphrase”, p. 143) – preserving Pushkin’s ababeecciddiff rhyme scheme (feminine vs. masculine rhymes) & technical metrical details, account for Russian & French (+ English indirectly through French models & translations) intertexts

The person who desires to turn a literary masterpiece into another language, has only one duty to perform, and this is to reproduce with absolute exactitude the whole text, and nothing but the text. The term ‘literal translation’ is tautological since anything but that is not truly a translation but an imitation, an adaptation or a parody. (p. 148)

- attainable ideal?

I want translations with copious footnotes, footnotes reaching up like skyscrapers to the top of this or that page so as to leave only the gleam of one textual line between commentary and eternity. I want such footnotes in the absolutely literal sense, with no emasculation and no padding—I want such sense and such notes for all the poetry in other tongues that still languishes in ‘poetical’ versions, begrimed and beslimed by rhyme. And when my Onegin is ready, it will either conform exactly to my vision or not appear at all. (p. 155)

- target audience of Nabokov's four vols. 1st edition (1964) with competence in languages, literatures, textual features?

2. Hardwick, “Translated Classics around the Millennium: Vibrant Hybrids or Shattered Icons?” (in Lianeri and Zajko, 2008)

- translations, adaptations, versions of (recognizable) classical texts: decolonize classic~translation relationship (“classical tradition”) by embracing translation’s inevitable hybridity as cross-fertilization of ST/TT, translation as interplay & braiding of texts, voices & identities, cultures, past & present, e.g. across genres, collage (reassembling shards), hybrid performances combining distinct traditions (e.g. east~west, African~European) vs. fear of miscegenation (classicists’ textual purity, nativism, fossilization & fixity of meaning, ownership, authenticity, fidelity, fetishizing icons)

- translation’s creation of dialogical spaces between, forging new relationships between source/target that “[disrupt] expected and settled cultural and hermeneutic relationships between the source and receiving languages and contexts” (p. 343): translation as dialectical, multi-directional reception minus hierarchical assumptions about subaltern status of target & invasive nature of translations; translations can alter views of ST (idiosyncratic & creative role of translation’s readers acknowledged)

- translation involves dynamic relocation of ancient texts within larger modern frames (aesthetic, intellectual, political, historical, etc.) requiring fresh, transformative, re-energizing translations & performances, “Dialectical reciprocity involves more than a balance sheet of ‘loss’ and ‘gain’. It actually changes conceptions of the source text and language and of the target context and language by creating a ‘text’ that is part of a new network of relationships between both” (p. 346).

- envisioning translation’s larger role in pluralist liberation from exclusive identity, nationalism & nativism

The study of constructions of authenticity and of the historical importance of attitudes to ‘roots’ and ‘origins’ will continue to have a role in understanding the various ways in which classical texts have ‘migrated’ from the ancient to the modern worlds, but a continuing obsession with purism will merely intensify the sense of limitation and isolation imposed by the perceived need to defend threatened territory . . . the hybrid and transformative energy of the translation (with all its provisionality) and the shattered icon of the source (with all its remaining potential for recombination) are both part of a broader mutual process of evaluation, understanding, and creativity. (p. 362f.)

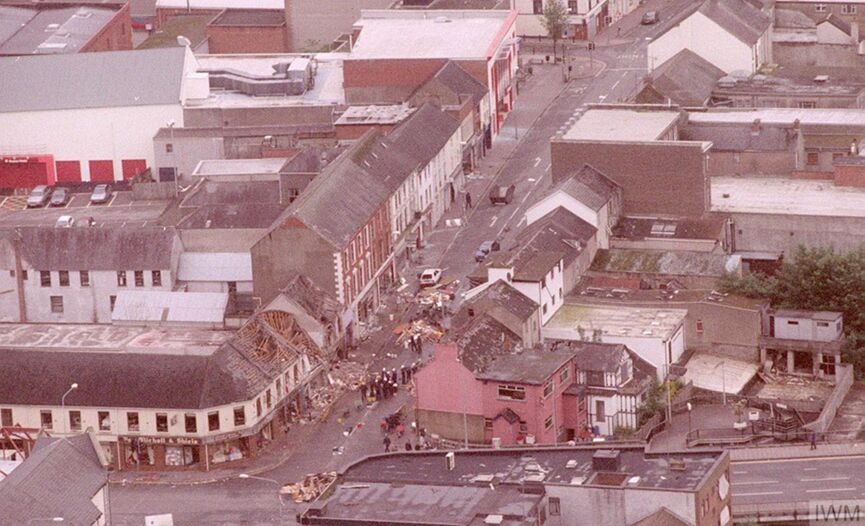

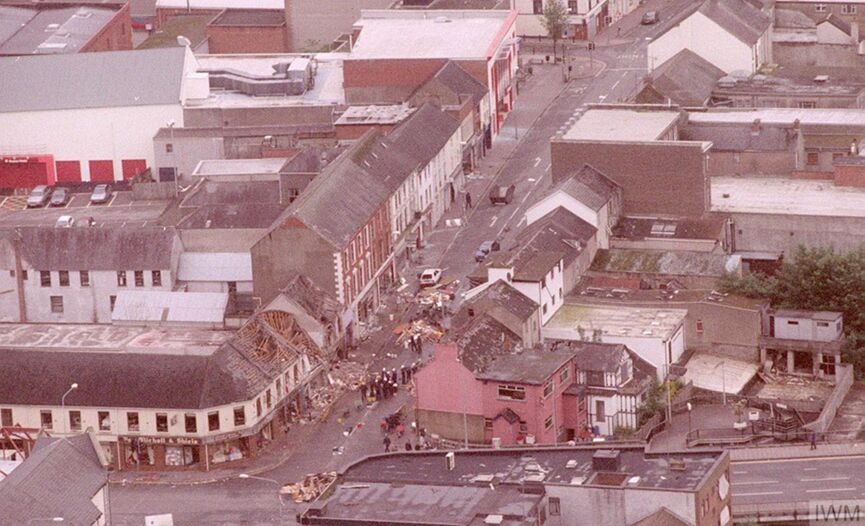

Seamus Heaney, Human Chain (2010), “Route 110”: lyric journey of shades & memories in Belfast during The Troubles mapped onto Aeneid 6 (cf. Heaney’s 2016 bilingual edition); @Poetry Foundation

Lee Bruer’s and Bob Telson’s The Gospel at Colonus: African-American Pentecostal tradition reframed as Greek myth (suffering, catharsis, redemption; cf. Oedipus’ transformation into hero in Oedipus at Colonus); American Music Theater Festival, 1985, with Morgan Freeman as the Messenger, The Five Blind Boys of Alabama as Oedipus; “Do Not Go On”; “Fair Colonus”;

3. Reviews of De Rerum Natura translations

Frantantuono (BMCR, 2008) on Slavitt: the Anti-Translator (“tedious lesson on how not to render Latin verse into English” – omissions, mistranslations, misunderstandings, sweeping assumptions about science, un-scholarly, Latin?), brief assessment with specific negative exempla, preference for existing translations that are “more Lucretius and less David Slavitt”

Todd (BMCR, 2002) on Smith 2001 (revised 1969 prose translation for American audience): some critical focus on skopos & utility (“not a tool for philosophical teaching”), 956 words, scattered comparisons with Lathan/Godwin’s Penguin

Jarman (Hudson Review) on Slavitt and Stallings: presumption that Lucretius is writing “epic-length essay . . . Lucretius told no story”? (poetry vs. philosophy?); comparisons with no Latin triangulation (readability of Slavitt vs. a pleasing Stallings)

McDonough (Sewanee Review) on Slavitt and Stallings: no triangulation with Latin (Slavitt readable & pleasant, more challenging Stallings’ fourteeners capture some of Lucretius’ archaic flavor)

Donoghue (Open Letters Monthly) on F. O. Copley (2011 re-issue of 1977 trs.): Copley “the most readable version of this poem every [sic] produced”; “virtually everything splendid about it derives from Copley, not [daffy] Lucretius”, Copley’s “gentle, tidal English does quiet wonders with the slipshod original Latin”; swipes at “blathering” Stephen Greenblatt’s “preposterous new book” = The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (W. W. Norton, 2011; Poggio Bracciolini’s 15th century quest for MS); misrepresentation of Epicureanism as “free of onerous moral obligations”